Statement

I want to reconstruct illustrations of classical astronomical instruments using ASCII art characters, exploring the evolution of knowledge media from material experience to computationalism. Through this, I aim to question the trend in contemporary science of over-relying on computational models. I simulate a ‘Ship of Theseus’ replacement process by gradually replacing parts of concrete, handcrafted instruments with characters. This experiment made me realize: when the components of science are replaced one by one with programmatic symbols, does it still retain the ability to truly understand the world? The project, which uses visual experiments as its method, focuses on this question: when science separates from perception and experience and relies only on abstraction and simulation, are we changing our direct understanding of the real world?

Reading list

- Mitchell, in What Do Pictures Want?, proposes that images possess “desires” and “agency” and are not merely passive carriers of information but active entities that shape cognition and understanding. This idea led me to rethink the role of characters in ASCII reconstruction: as I gradually replace the images of scientific instruments with data symbols, the medium of the image shifts, fundamentally changing the way it carries knowledge. I see this process as an active “translation” of images from perceptibility to codability, rather than a simple transformation of form. By breaking down classical scientific images into characters, I simulate how knowledge gradually detaches from bodily experience as the medium evolves. Mitchell’s discussions on the social life and performativity of images made me realize that this replacement is not a neutral act but a performance about how scientific knowledge is continually “reconstructed” within a symbolic system. At the same time, this raises a crucial question: in this reconstruction, is science losing its ability to directly understand the real world? This is the core crisis I aim to address through image experimentation.

Mitchell, W.J.T. (2005). ‘What Do Pictures Want?’. In: What Do Pictures Want: The Lives and Loves of Images. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, pp. 28–56.

- As mentioned in this article, design plays a role in modulating, reshaping, and negotiating an interface between users and the world, over which designers have profound control.The classical scientific instrument illustrations I chose represent a specific “world” – a world in which scientific knowledge is recorded and understood through concrete, observation-based and painting-based visual forms. This form itself is an interface between users and knowledge.I want to manipulate this manipulation of form using ASCII characters. ASCII characters are completely different from the painting form of illustrations. This intervention and replacement of form creates a new “interface”. When viewers watch, they are no longer just facing a pure painting image, they must negotiate this interface that mixes illustration and ASCII.

2×4. (2009). Fuck Content. Available at: https://2×4.org/ideas/2009/fuck-content/ [Accessed 21 April 2025].

Theme related

Yuan-Sen Ting (2024) points out that even under high-quality data conditions, machine learning models systematically underestimate extreme values when analyzing astronomical spectra due to “attenuation bias.”

Although these data models are more precise than human observation and calculation in extracting information and processing large volumes of data, they are fundamentally based on statistical assumptions. If there is any measurement uncertainty in the input data, even a small amount, it can lead to systematic distortion in the output. This leads to the conclusion that the efficiency of algorithms does not equate to a “neutral” or “true” representation of the universe. This bias not only limits our understanding of extreme astronomical phenomena but can also lead to misjudgments in key theories like cosmic evolution. Therefore, relying on algorithms without acknowledging their limitations is a misunderstanding of scientific cognition.

Ting, Y.-S., 2024. Why Machine Learning Models Systematically Underestimate Extreme Values. arXiv preprint arXiv:2412.05806. Available at: https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2412.05806 [Accessed 20 April 2025].

Medium related

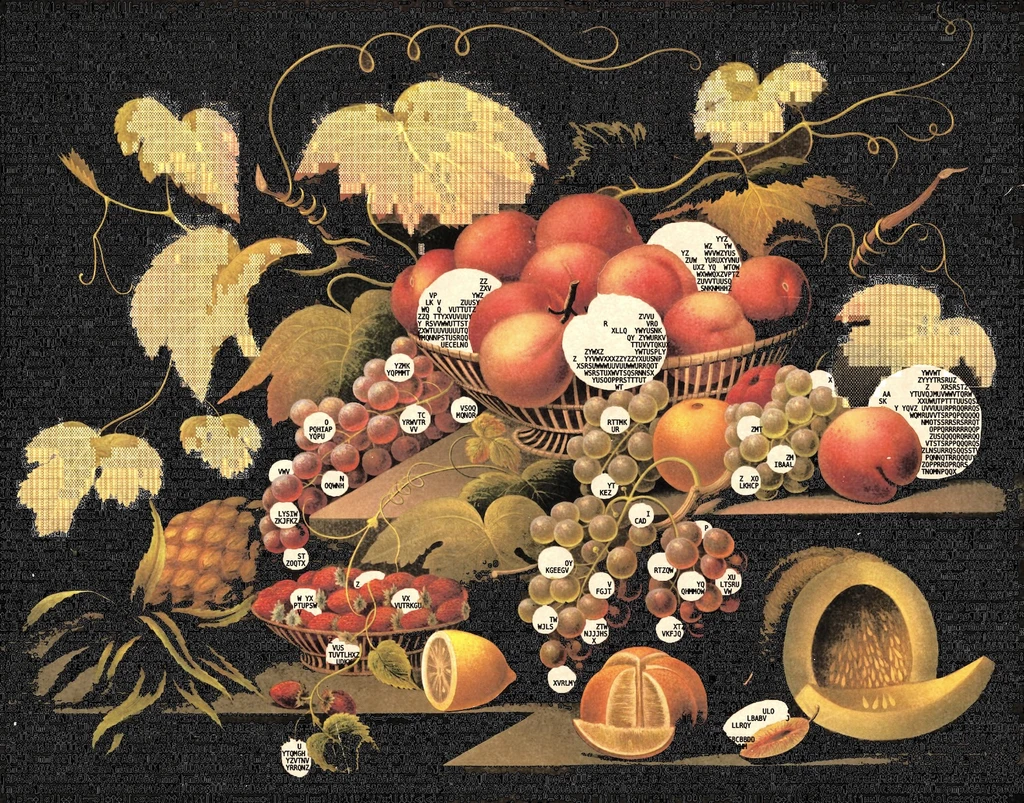

This work combines traditional still life painting with ASCII characters, maintaining the retro composition of 17th-century still life but replacing certain areas with ASCII art effects. The characters do not fully replace the image but coexist with the original, creating an environment of multiple meanings. I see this “visual interference” as a form of emphasis, forcing the viewer to reconsider the essence of the image. It turns design into a tool for criticism and expression, not just decoration. This approach is similar to my own method of exploring the variability of image information, revealing how images can create new meanings and interpretations in different media and contexts. It inspires me to express the transformation and instability of images through “destruction” or “manipulation.”

Enigmatriz. (n.d.). ASCII Art. Available at: https://enigmatriz.com/artworks/ascii-art [Accessed 1 May 2025].

Critical position

The Ship of Theseus paradox originates from ancient Greece: The ship of Theseus is preserved as a memorial, but over time, the planks of the ship are gradually replaced until no original plank remains. The question is: is it still the original Ship of Theseus?

This paradox not only challenges our traditional understanding of object identity but also raises important questions about the relationship between form and change. As time passes and parts are replaced, does the core “materiality” of the object persist? This is not just a transformation of the material, but a reconstruction of cognition and perception.

When the “materiality” of tools and objects is abstracted into data characters, do we still view them as “that object”? I use symbols as “materials” in my creation process, where characters are both destructive and constructive—dissolving the materiality of the object while establishing a new symbolic existence. This transformation of materials leads me to rethink the boundaries between objects, images, and language. It makes me realize that an object’s “existence” is no longer defined by its physical composition but by how we construct and understand it through images and language.

Cohen, S.M. (n.d.). The Ship of Theseus. University of Washington. Available at: https://faculty.washington.edu/smcohen/320/theseus.html [Accessed 2 May 2025].

Wild card

I read the “Typewriter” section, where the shift from handwriting to typing no longer extends bodily action but becomes a quantifiable, standardized operation. As Kittler points out, the arrival of the typewriter dissolved the intimacy and individuality of handwriting, transforming “writing” into a neutral process of text handling. This shift not only changed the way we express ourselves but also altered our cognitive structure—leading us to increasingly organize language in a clear, linear fashion, prioritizing speed and efficiency over emotion and traces. The change in medium pushes us from “perception” to “coding,” breaking the world down into operable symbol systems. We no longer understand things through bodily experience but through abstract operations using keyboards, characters, and formats. This change is not just technical; it is reshaping our very ability to understand. It is making our perception of the world more symbolic and de-emotionalized, fundamentally altering our understanding of the concept of “understanding.” From traditional sensory understanding to modern symbolic operations, we are losing an intuitive connection with the world, replaced by a highly abstract, algorithmic cognitive structure.

Kittler, F. (1999). Gramophone, Film, Typewriter. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, pp186-187